Castelli SkillZ and DrillZ Ride, 17 May – Did it happen again to you? You felt great going into the end of a race, so you launched yourself off the front of the race. The initial surge got you three bike lengths, and you could see the finish line rapidly approaching. Just when you think you have it all sewn up, three or four riders blow right by you, leaving you wondering what just happened.

Dont’t worry. You are not alone.

What if I were to tell you that it happens to professional riders all of the time? Would you believe me? Check out the end of Stage 15 of the Giro d’Italia on 21 May. Simon Yates from Orica Green Edge launched an attack with 300 meters to go, only to get pulled back with 50 meters left to finish fourth.

What If I told you there exists a strategy that will greatly increase the chance of success of your attacks? Would you believe me? Mikael Kwiatkowski used the strategy to great success multiple times this year, including his masterpiece win at Straade Bianchi, which I found more impressive than his win at Milan-San Remo.

Timing is Everything

During SkillZ and DrillZ, we talk about timing quite a bit. Picking the time to launch an attack or repeated attacks is often the deciding factor on whether you escape or not. That timing is often crucial to whether you stay away if you manage to escape. Unless your goal is to get TV time for your sponsor, a flashy attack that results in getting caught and spit out the back is no more useful than getting dropped early on in the race.

Drill 1 – Attacking on the Incline

The first drill of the day focused on attacking the group on a short climb. We have covered attacking on short climbs before, but this time we looked at it from the perspective of the finish line not being at the top of the climb. No, the short climb would be the set-up to get away from the sprinters and downhill specialists.

Attacking on the climb is no different than any other attack, except gravity gets to play a part. Due to that, I often try to avoid attacking from the bottom of the climb to limit the amount of time I have to fight against nature. Also, the bottom of most climbs on Zwift are often not very steep. No, the hard ramp usually happens in the middle. That’s when I like to go, when it gets really hard.

Why? Well, I’m already going to have to go hard because of the increased pitch, so what’s a little deeper grab into the pain bank if the duration is short? Not much when you consider the upside.

The second key to attacking on the short climb in an effort to escape is holding it through the crest and down the first third of the descent if one follows the climb. If there is no corresponding downhill section, you need to hold the hard effort for a few minutes after the climb ends.

Yes, it sounds horrible and painful. It is. I’m not telling you it is easy to escape on a climb. This technique works, though, because everyone wants to briefly sit up after a hard climb and catch his or her breath, especially if you roll into a descent. It is a natural response to stop the pain if given the option. Escaping requires you to fight that natural urge.

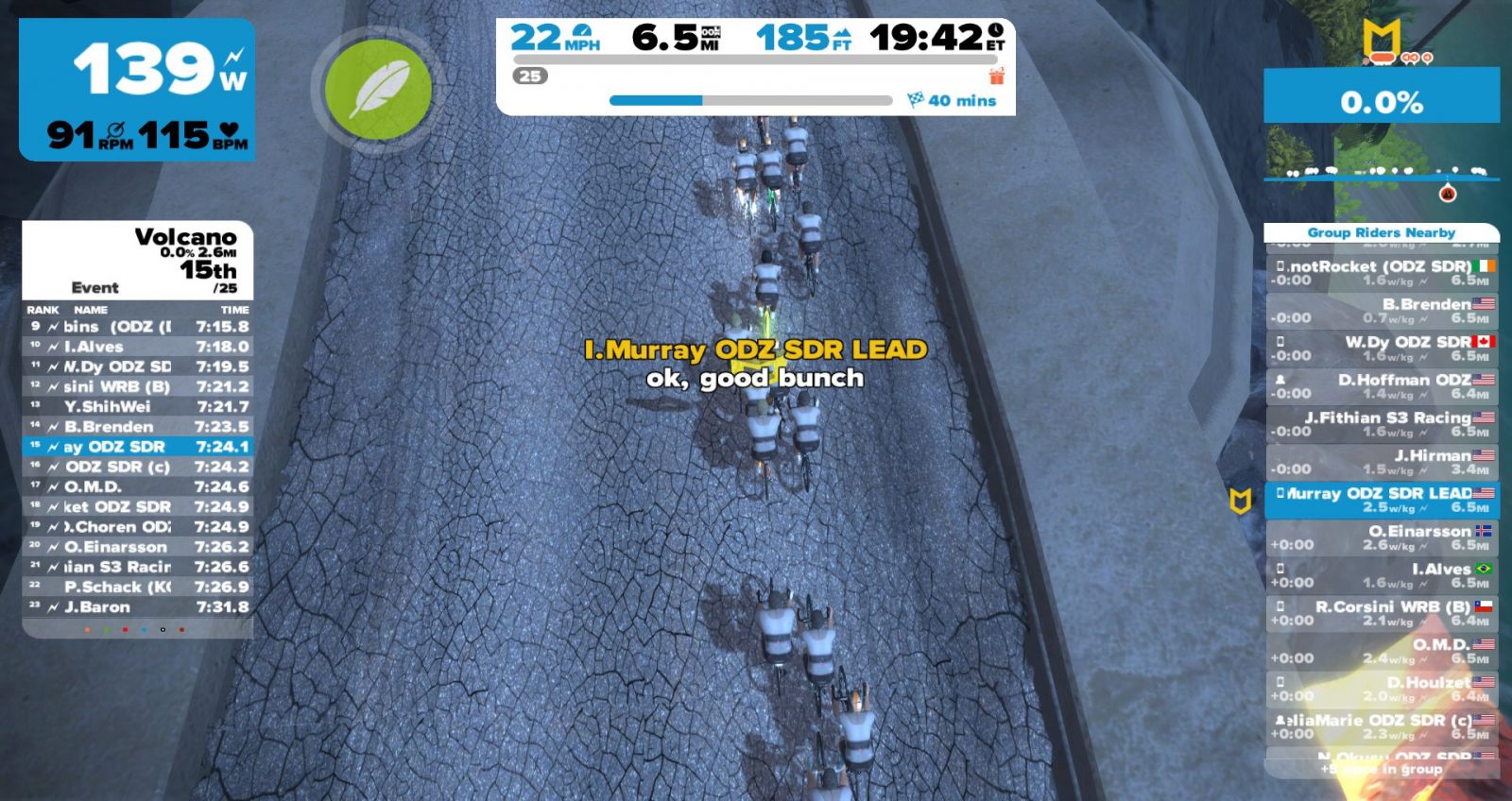

We practiced a number of attacks on the Volcano CCW course on the short, steep climb heading into the finish line/lap counter and on the short, but not quite as steep climb just before the windy descent to finish the lap. The biggest immediate gaps opened on the first climb, but the bigger gaps over the duration occurred when attacking the climb before the descent. We’ll cover why that is the case during Drill 2.

The key to success for Drill 1 was going hard enough to get a gap but not going so hard that the attacker blew up before cresting and continuing on down the road. After a few iterations, we were able to see that everyone’s launch point was different, but the end result was the same, a gap and an opportunity.

Drill 2 – Attacking the Downhill

What happens if you are surrounded by little climbers or Philippe Gilbert types who love those punchy, short climbs? If you aren’t one of those, then attacking on that terrain is tantamount to handing someone else the victory. That’s what we call the opposite of smart racing tactics.

In this case, we have to look for better options. If you are a heavier rider who packs a good kick or a death-defying daredevil, you may want to look for an opportunity to launch an attack on a downhill section of the race.

Attacking the downhill is one of those instances where Zwift and IRL racing diverge but only once on the downhill. I say that because a downhill attack does not start on the downhill. No, it starts at the last little kick rolling into the crest of the hill. That’s where the gap happens.

Once the gap opens, it’s time to ride like hell to reach your maximum safe speed as quickly as possible. If you are not a very skilled bike handler, I wouldn’t recommend this type of IRL attack. Stick to Zwift. The important part is keeping the effort high. On Zwift, rider weight plays a significant role in longer downhills, so take that into account. On the Volcano CCW course, weight does not seem to play as much of a factor on the steep downhill after the second pass through the volcano.

We practiced this technique a few times in the group, and those who hit the gas hard before the crest started the descent with much more momentum than those who did not treat it as a vicious attack. Carrying speed out of the climb is key.

Understand that your ability to accelerate to faster speeds on the descent takes more energy per relative mph gain than going uphill or on the flats. That’s because the gravitational advantage applies to everyone, and the faster you are going, the more energy it takes to go faster. Likewise, your gearing becomes a factor, too, as you may run out of gears with power still left in the legs.

Yes, that’s the dreaded spin out on a smart trainer. Before you know it, you are in your smallest cog, spinning like a crazy person at 125 RPMs, and bouncing up and down on your saddle like you are riding a bucking bronco. (Note: lowering your trainer difficulty can help with this.)

That effective use of inertia is the key to Drill 2. Keep in mind that you need to ride within your skillz, so make sure that you are technically competent before attempting any of the crazy stuff out on the road. Oh, and watching pro riders descend like lead balloons on television does not mean that you have skillz. It just makes you a fan, like me.

Drill 3 – Attacking from Distance

Yatesy the Sprinter?

Now that we walked through some of the drillz, we have to incorporate our knowledge of the course and the conditions into the development and implementation of the strategy. Let’s examine our two examples from the beginning, Adam Yates and Mikael Kwiatkowski.

Looking back at our Giro example, Adam Yates made a decision based on a faulty assumption. He thought for a minute that he didn’t suck at sprinting.

WRONG! He does.

Ok, it’s not so much that he is a horrible sprinter, but relative to Bob Jungels and Tom Domoulin on a race course with a slight downhill finish, Yates’ attack was horribly timed. Of course, we have the luxury of hindsight, and he was flush with lactic acid after a short, steep cobbled section to finish off the 200-kilometer day. The only chance Yates had to succeed was to launch from just beneath the crest of the finishing hill. I say that because there were too many big names with fresh-ish legs at the base of the climb, and nobody wanted to lose time, resulting in a chase of every attack. Just before the top, though, the lull happened, as the GC contenders all began to crest. That would have been the only opportunity for Yates. Sure, it would have been a longer attack, but the early momentum may have carried him, as his legs began to give out.

History Favors the Bold

Mikael Kwiatkowski is a true rolleur. He can climb well enough, sprint well enough, and time trial well enough, but he cannot compete with the specialists in those disciplines. No, he is simply very good across the board but not great at anything.

Except for picking the time to attack. He is exceptional at that. In Strade Bianchi, Kwiatkowski found himself in a group with some exceptional finishers. The remaining portion of the race featured rolling and windy terrain on crappy roads that favored a small group or an individual over a large peloton. Rather than wait until the last few kilometers to attack or sprint against some top class sprinters, Kwiatkowski went from distance.

It worked, and he was deemed a genius. He wasn’t a genius, though. He simply made a calculated decision. Kwiatkowski attacked hard enough to get a gap and quickly consolidated that gap, knowing that the remaining contenders would not immediately work together to pull him back. How did he know this?

Well, it was pretty simple. None of the major contenders had many teammates left in the chase pack, and nobody who wanted to sprint for the win would be willing to drag 20 other riders to the finish line. Thus, he calculated that the disorganization would allow him enough time to build a big enough gap that only a well-organized chase would be able to pull back.

Of note, when Kwiatkowski got out of sight of the chasers, he settled to a hard but manageable pace, really only burning matches to get away and to close out the last few kilometers. Other than that, he pushed but stayed within himself, the secret to the long-distance attack.

Guaranteed Success or Your Money Back

Ok, nothing guarantees success in a bike race other than being the only racer. The strongest rider doesn’t always win, and luck sometimes favors the stupid. However, if you take into consideration the other racers in your group, the race conditions, and your relative strengths, you can pick a much smarter attack strategy.

It won’t always work because the enemy gets a say on any plan you develop, but your odds of succeeding increase significantly if you have a plan vs simply playing it by ear or reacting to the other racer.

Over time, you will get a lot better at picking when to make your attacks to ensure that you maximize your chances. Increased knowledge of your opponents and familiarity with the race course are hugely helpful and can give you a good advantage. In the end, once you make the decision to attack, commit. A well-timed but half-hearted attack will fail virtually every time. However, a well-executed attack, even if not perfectly timed, at least will put you in the running for the win.

SkillZ and DrillZ will be back on 31 May for some fun efforts. We will be back at it full force all summer long for the northern hemisphere types and all winter for those south of the equator. During the break, keep trying to add the lessons from previous classes into your racing and group riding to work on your tactical prowess. Until next month, RideOn!