Am I super-efficient, or just heavy?

That was my first thought when a fellow Zwifter commented on my recent race, “Somehow you always get your w/kg down. Great drafting skills!”

Here’s the thing: I probably am a fairly efficient racer, when I want to be. I’ve done multiple races where my main goal was to keep the watts as low as possible while hanging with the front group. I did this because I had a particular effort level planned for my workout that day, and didn’t want to exceed it. But I also did it because I knew it was great practice! Conserving energy is a key part of successful bike racing. (It’s not the only part, of course! Knowing when to go hard and having the fitness to do so are also vital skills.)

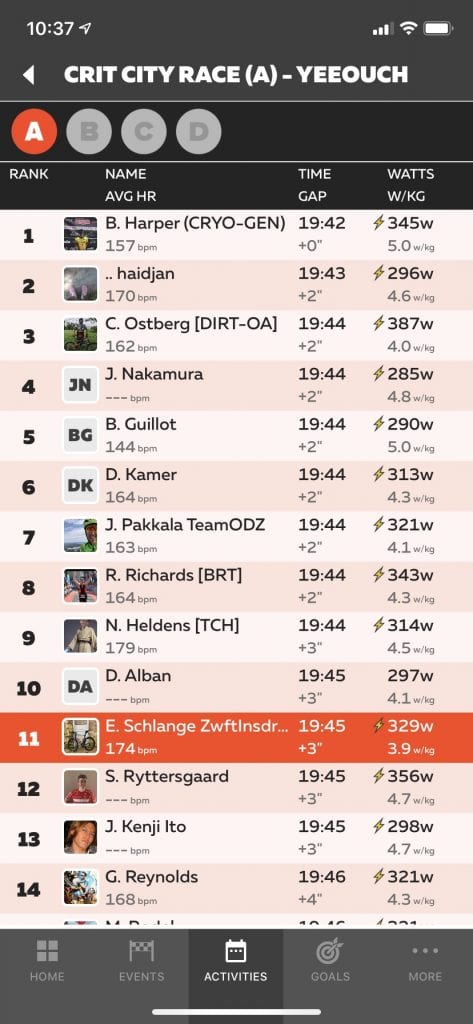

My best race results as a Zwift B are on flatter routes, and I find my watts per kilo are consistently lower than most of the riders around me. A recent Crit City A Race is a very good example of this: I finished in the front pack, sprinting it out for 9th place. My 3.9w/kg (a new PR!) was the lowest of top 15 riders. In fact, the only riders at or below my w/kg were minutes off the back.

So am I a super-drafter, the king of indoor efficiency? I don’t think so. I think I’m just heavier than my competition. Case in point: in the A race I mentioned, only one rider was heavier than my 85kg dad bod.

Which brings me to today’s topic: reverse weight doping.

Weight Doping: an Introduction

On Zwift, “weight dopers” seek to gain an advantage by entering a lower-than-life weight into their Zwift profile. Since we know that lighter weight=higher virtual speed, this is a very easy way to cheat the system on Zwift.

Weight doping is a key challenge for cycling esports to overcome, and it’s one reason why many “big” races (e.g., those with prize money) require riders to show up and weigh in on-location in a supervised environment. It’s also why the Zwift Transparency Facebook group was created, where racers post videos of themselves weighing in using a particular protocol which makes it difficult to fake your numbers.

Some weight dopers are obvious and blatant – other times it’s much less egregious. Example: have you ever purposely avoided weighing yourself (especially you who have a Withings scale that automatically updates your Zwift weight) because you know you’ve put on a few pounds over the weekend? I know I’ve done it!

Some Zwifters go so far as to social-stalk other riders, comparing their photos to their Zwift weight and calling them out for weight doping. (I don’t recommend this approach, but it proves the point that weight doping is an issue that concerns many Zwift racers.)

Reverse Weight Doping

So what is “reverse” weight doping? Well, it’s adding weight to gain an advantage. “How does being heavier help a cyclist?” you may ask. Good question. It all has to do with the way Zwift’s racing categories work. The categories currently used in most Zwift events are based on your FTP watts per kilo–that is, your FTP in watts, divided by your weight in kilograms. (Example: if your FTP is 300 watts and you weigh 75kg, your FTP w/kg would be 300/75, or 4 w/kg.)

The race categories end up looking something like this (taken from the current Tour of Watopia race events):

- A: 4-5 w/kg

- B: 3.2-3.9 w/kg

- C: 2.5-3.1 w/kg

- D: 1-2.4 w/kg

ZwiftPower, home of official race results for community races, adds some pure wattage breakpoints to the above list to help lightweight riders stay competitive. But for most riders watts per kilo rules the day, determining which category you race in Zwift. And this is why reverse weight doping is a thing.

How does it work? Well, imagine you’re a strong C racer. You weigh 80kg and have an FTP of 248 watts, which works out to 3.1 w/kg. But you’re training and racing and getting stronger, and eventually your FTP improves to 260 watts, which is 3.25 w/kg. Nice work! But there’s one problem: this puts you into the B category, and you don’t want to race the B’s. You’re having fun winning (or nearly winning) C races!

What’s the cheater’s solution? Gain a few (virtual) pounds. Bump your Zwift weight up to 84kg and even with your new and improved 260-watt FTP you’re only at 3.1 w/kg! You’ll move a little slower with the added virtual weight, but you’ll be able to hang with the front of the C’s instead of getting shelled off the back of the B’s.

Scale of the Problem

How big of a problem is reverse weight doping? I have no idea. I’m sure it happens, but I would guess it’s pretty rare – certainly less of a problem than “normal” weight doping.

But it highlights a bigger problem, and that is the fundamental flaw of using watts per kilo for race categorization. When a rider can change categories by modifying their virtual body weight, that’s an issue. It points to the need for a results-based categorization system, which I discussed a month ago in the final post of my race category series.

When It’s NOT a Problem

I should mention: many Zwifters have “lied” about their in-game weight for perfectly acceptable reasons. If it’s not done during a competitive Zwift event, I don’t see it as a problem. You do you. I once made myself much heavier so I could compete against my 11-year-old son in a head to head Zwift climbing race. He had fun laughing at fat dad, but I pipped him at the line!

If you’re a 300-pound dude who wants to go a little faster uphill as a virtual 200 pounder, have at it. I wouldn’t personally do it since it throws off training metrics and just… isn’t true. But you’re not affecting anyone else’s experience. Weight doping is only a serious issue when it’s done in competition.

Your Thoughts

Are you efficient, or just heavy? Do you believe weight doping (reverse or otherwise) is a big problem in Zwift racing, and if so, what can be done about it? Share your thoughts below!