Competitive Zwift Racing, at the nexus of video games, exercising, and competitive team sports, is pushing the boundaries of how we think about competition. In the first part of this series we looked at the population of 80,000+ riders that participate on the ranked ladder – a truly global audience, often racing weekly – and the most popular events. And in a follow-up article we looked deeper into the demographics of that population – it’s quite different than what you might imagine the typical “esports” competitor looks like.

But after all of that “context setting” I still had significant questions about the outcome of all that competition. Categories, sandbagging, and weight-doping are certainly some of the hot-button topics in the community (though, potentially not more so than other competitive esports where terms like “smurfing” are similar lightning rods).

The difference between Zwift and other esports is there isn’t currently any concept of matchmaking – when you click the “join race” button, there is absolutely no guarantee you have a fair shot at winning. Zwift has recently started experimenting with “category enforcement” where you might be excluded from some races based on previous performances. This is a solid half-step toward a level playing field.

But is a level playing field on every race the right end goal? Sure in other esports, competitive games are all about winning each match – but in Zwift, for many (most?) it is simply a great way to get a good workout in. One interesting direction to look at is the race ranking that ZwiftPower tracks for each rider which turns each race into a meta competition across all 80,000 racers, not just those lined up next to you.

There is a great overview of the mechanics here and strategies for improving it here, but I had some fundamental questions about the whole system:

- Should I care about rankings? Are the rankings actually predictive of performance? Are better ranked riders actually more likely to win?

- What is an appropriate rank goal for me? How would that change as my power curve improves?

- How should I think about Cat B riders that are ranked better than many Cat A riders? Should I be aiming to get to the top of my own cat rankings? Or just ignore category rankings and climb as high as possible?

Ranking Landscape Today

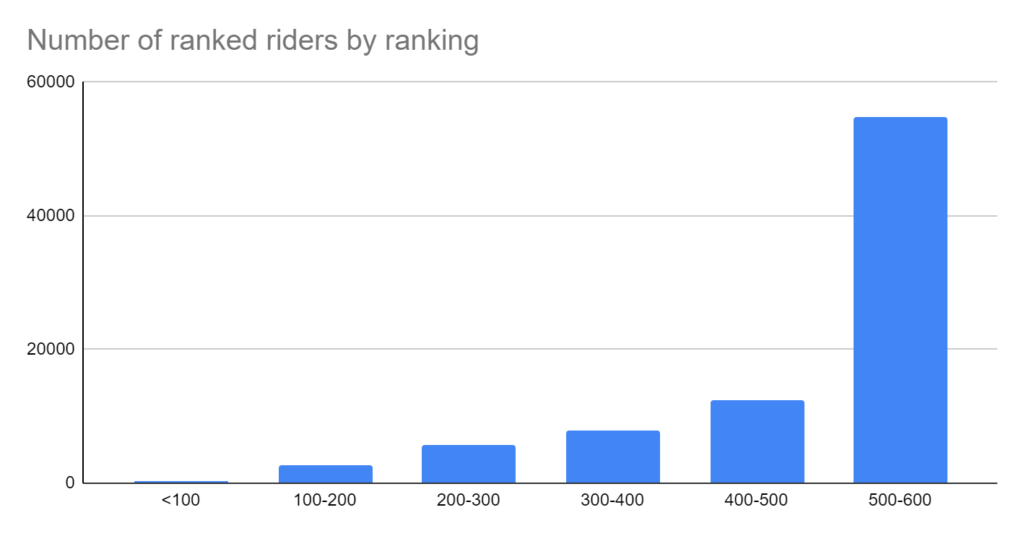

Based on the way rankings are calculated (best 5 races in the last 90 days), you really need to be racing at least 2x per month in order to have a rank that has a chance of accurately reflecting your performance. If you have fewer than 5 ranked races in the past 90 days, the algorithm assigns you a rank of 600 (the max) for the missing races which will tank your average.

Per my last post, almost half of the racing community races 1-2x per month, which leads to a huge chunk of ranked riders with a rank of 500-600 simply due to having missing data points. Beyond that, the distribution of riders by rank declines fairly linearly – this would suggest going from rank 300 -> 200 is harder, but not exponentially harder than going from 400 -> 300.

| <100 | 100-200 | 200-300 | 300-400 | 400-500 | 500-600 |

| 0.3% | 3% | 7% | 9% | 15% | 65% |

[Methodology note: similar to the last article, population at each ranking range was estimated by finding riders ranked exactly “300” and looking at what their overall position was (so a rank 300 rider is reported as “in 9,000th place overall” this means there are 9,000 riders ranked between 0-300. Similar methodology was used for the below category breakdown chart.]

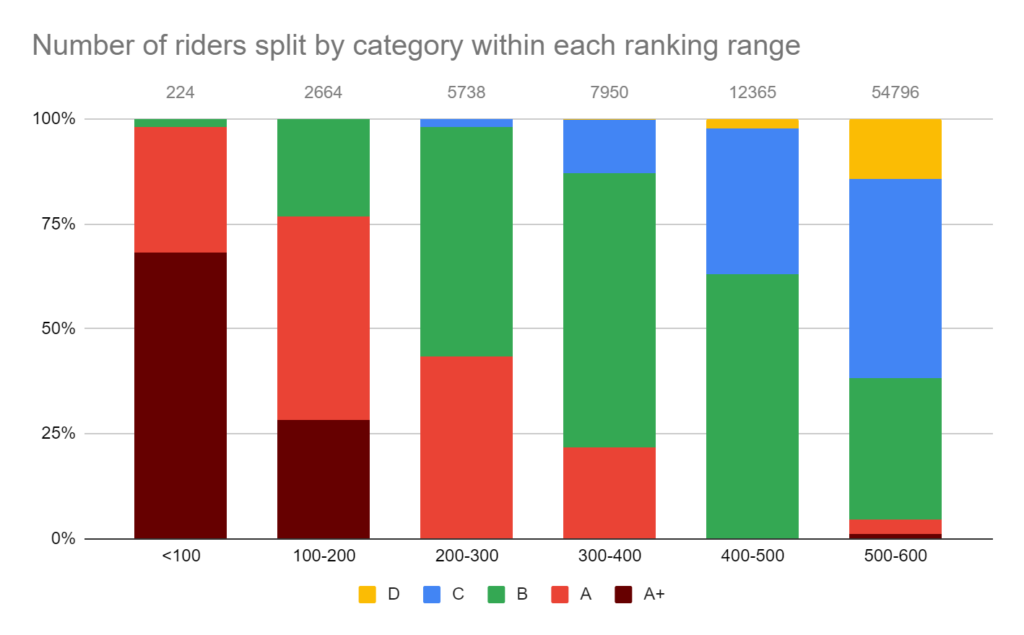

The other thing to note is the significant overlap in rankings between categories. There are many category B riders ranked ahead of category A riders. Similarly for the line between A and A+ and the line between C and B.

More on this overlap later, but my first question was around how important really are these rankings within a category (given folks usually race within their category)? How big of a deal is a 50pt difference? What about a 200pt difference?

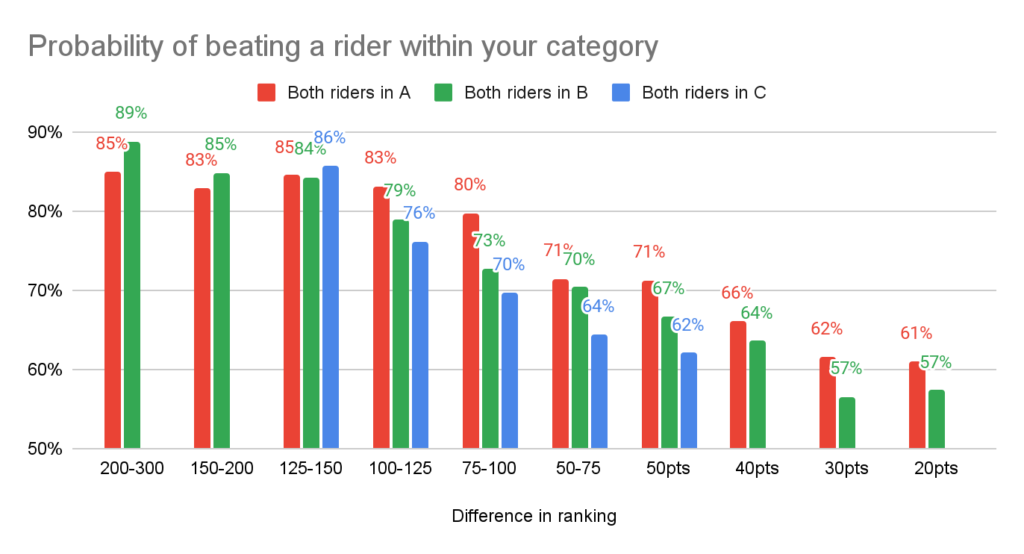

[Methodology note: in the above, I took a random sample of races, broke each race down into a bunch of 1v1 races between each of the participants within each category, and looked at how frequently a rider of a given rank finished ahead of a rider ranked XXpts below them regardless of their overall finish position – so the 2nd to last place rider “beat” the last place rider. I also excluded the 65% of riders from the analysis ranked 500-600 given they may not have the full 5 races of data so their rank is less indicative of actual strength. Because the C & D categories have significantly fewer riders ranked less than 500, we can see some partial data for C, but are missing D data entirely.]

It turns out rankings are relatively predictive of performance. If you line up next to a rider in your category ranked 100pts better (lower) than your own race ranking, you have ~80% chance of finishing behind them at the end of the race (though 20% of the time you will beat them!). As might be expected, small point differences matter a lot more in category A than in B & C where a <50pt difference only gets you a small bump.

So what is a good ranking goal to shoot for? To try and put some guardrails around a reasonably achievable goal, I looked at the average performance of riders with different rankings in actual races. This should give me a sense “if I wanted to ride like a rank 200 B rider,” what kind of power I would need to put out in a typical race.

| A | <100 | 100-150 | 150-200 | 200-250 | 250-300 | 300+ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20min w/kg | 4.3 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 4.3 | 4.1 | 4.2 |

| 5min w/kg | 5.0 | 4.9 | 4.8 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 4.6 |

| 1min w/kg | 8.2 | 7.4 | 6.9 | 6.6 | 6.4 | 6.1 |

| 15sec w/kg | 12.2 | 10.8 | 10.2 | 9.1 | 8.7 | 8.1 |

| B | 150-200 | 200-250 | 250-300 | 300-350 | 350-400 | 400+ |

| 20min w/kg | 3.6 | 3.6 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.6 | 3.4 |

| 5min w/kg | 4.3 | 4.2 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 4.0 | 3.9 |

| 1min w/kg | 6.2 | 6.1 | 5.6 | 5.5 | 5.2 | 5.1 |

| 15sec w/kg | 9.9 | 8.9 | 7.8 | 7.4 | 7.3 | 7.1 |

| C | 300-350 | 350-400 | 400-450 | 450-500 | 500-550 | 550-600 |

| 20min w/kg | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.1 | 3.0 | 2.9 |

| 5min w/kg | 3.5 | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.2 |

| 1min w/kg | 5.1 | 4.5 | 4.6 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 4.0 |

| 15sec w/kg | 8.0 | 6.5 | 6.6 | 6.0 | 5.3 | 5.4 |

| D | 450-500 | 500-550 | 550-600 | |||

| 20min w/kg | 2.3 | 2.2 | 2.3 | |||

| 5min w/kg | 2.8 | 2.5 | 2.6 | |||

| 1min w/kg | 4.0 | 3.4 | 3.3 | |||

| 15sec w/kg | 6.0 | 5.4 | 4.6 |

A couple of interesting points:

- 20min w/kg is pretty consistent across rankings within a category – this is likely just the pace of the peloton, no reason to push harder than the front group is cruising. In reality, top-ranked riders very likely have higher max 20min w/kg numbers than lower ranked riders, but they arent hitting those in typical races

- You start to see a gradual ramp up in 1min and 5min power output as you get higher rankings, this is the “don’t get dropped on hills by the front group” power output needed

- And then lastly, the 15sec power output seems to be the real differentiator, as would be expected given the importance of the sprint to actually winning races.

The important takeaway for me here was, based on my race power outputs, I should be able to stick with better-ranked riders than myself. Just need to get after it! - Lastly, worth pointing out the overlap across categories. A rank 200 A rider is putting out higher 20min, 5min, and 1min power output vs. a rank 200 B rider (the “don’t get dropped” requirements of the cat) but actually fairly similar 15sec power. Same for the overlaps between B & C, and C & D.

So could a rank 200 B rider beat a rank 200 A rider? Are top-ranked B riders “just cruising” during most races and could actually hang with, and frequently beat Cat A riders when racing head to head? Said another way, when I think about the overall stack ranking of Zwift, should we put all cat A racers above all cat B racers – or just ignore categories all together and use race rankings? The answer is definitely “it depends” but we could at least look at some data to help.

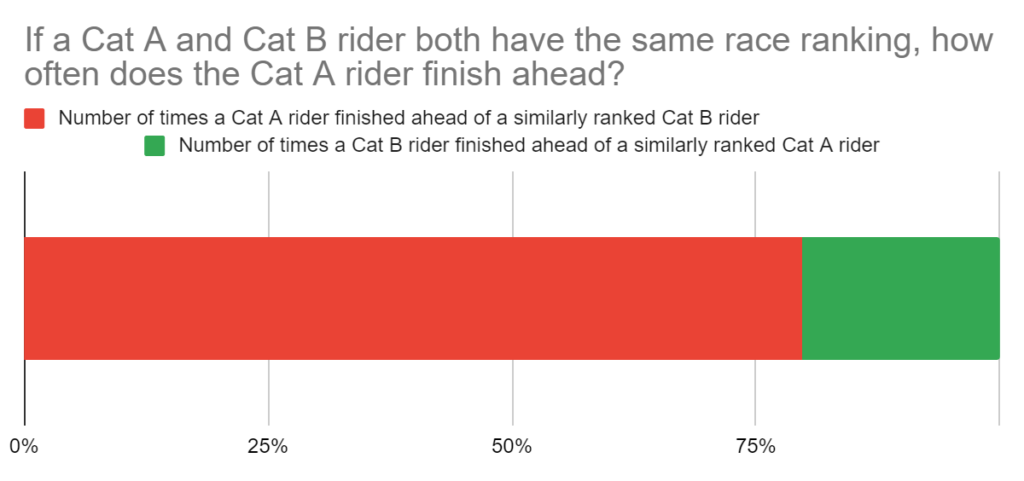

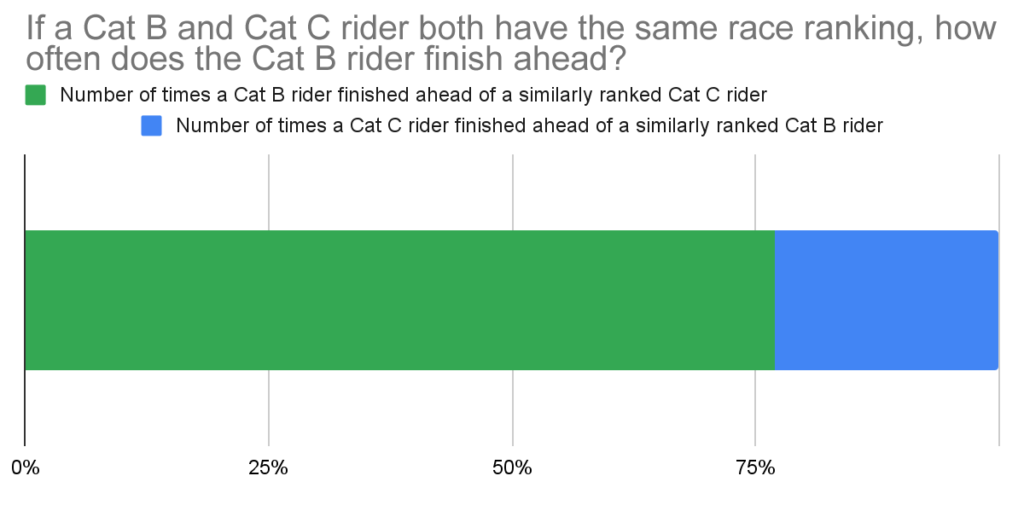

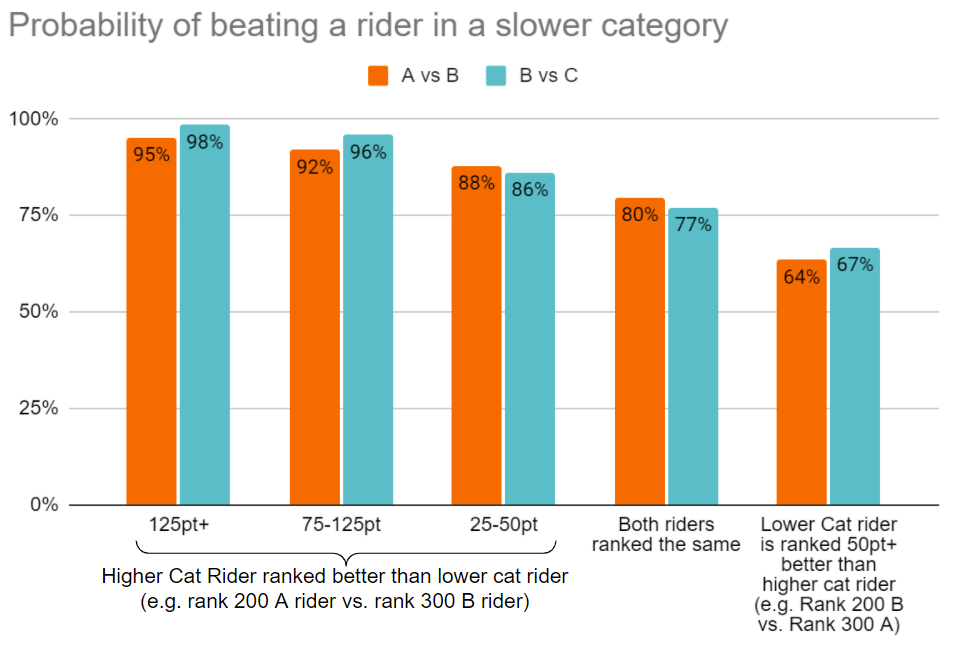

To take a crack at answering this question, I narrowed in on races where all categories start together – in these races (largely hosted by 3R) while a category B rider isn’t officially competing for a podium spot with a category A rider, they are riding side by side, so comparing the finish times of riders across categories should allow us to do a similar analysis. In the below charts, I looked at instances where a Cat A and Cat B rider (and then Cat B and Cat C in the 2nd chart) both had the same race ranking in these races. For Cat A/B this overlap occurred with both riders ranked between 200-300 most frequently; for Cat B/C this ended up being in the 400-500 range.

It turns out, the vast majority of the time (~80%), the higher category rider finished ahead. Looking back at our earlier win percentages within a category, an 80%+ likelihood of winning correlated to at least a 100pt difference in ranking, often even higher. So at a minimum, if you wanted to stack rank all of Zwift by race ranking alone, each higher category should get a 100pt+ bonus (e.g. a 300pt cat A should be ranked at least as fast as a 200pt B).

For the sake of completeness, I also looked at win probabilities of riders with different rankings across categories:

Maybe the most interesting bar is the far right bar where we look at riders in B (or C cat) actually ranked better than a rider in A (or B cat). Even in these situations, the higher category rider is more likely to win, even though they have a worse rank. This data, at least, would suggest that in the stack rank of all Zwift riders, category comes first, then ranking matters a lot within categories.

So where does this leave us, hundreds of thousands of data points and a few too many charts later?

- The competitive Zwift Racing Ranked population is somewhere around ~80k riders (maybe 10% of the total Zwift population), who each race about once a week, come from all over the world (though weighted toward Europe), and all age ranges (with the average somewhere in the 40s)

- Racing is clustered around ~4-5 major event organizers who are often hosting 100+ events a week, each with ~40 racers

- The vast majority or ranked racers compete in B and C categories

- The ZwiftPower race rank system does provide a fairly predictive way of stack ranking racers within a category

- However, despite the fact there is significant overlap in race rankings between categories, the data would suggest racers in a higher category are indeed faster than racers in the lower categories, even if the lower cat riders have achieved a stronger rank

Generally, I wish that last bullet was not true and we could develop an absolute measure of a racer’s relative strength that was predictive both within and across categories. That would take some of the pressure/importance off of the categorization system which is imperfect in many ways.

Your Thoughts

Share below!