Castelli SkillZ and DrillZ Ride, 3 May – We’ve all been there. In the middle of a group ride or race, our attention wanders because the pace is not high enough to force us to narrow our focus. After yet another in-depth examination of the stem or the socks of the rider in front of us, we look up and see a sizeable gap just ahead. Nobody attacked, and the pace isn’t particularly hot, but you are somehow dropped on yet another group ride. This time, there is no sweet satisfaction of the burning legs and lungs that normally accompany this vision. How did this happen?

All races and group rides are not created equal, and a course profile does not give you much more of a story than a book cover does. Yet, we often think that we can predict how a race will unfold simply by looking at the graphical depiction of the terrain.

Are we really that senseless?

Sometimes, yes, we are.

Don’t Sweat the Small Stuff (at Your Own Risk)

Everyone knows that a major climb is probably decisive terrain for most events. But this is just scratching the surface of what can affect a race. Rolling hills, crosswinds, and technical portions of a course can be and are often just as decisive as any alpine mountain. Just wait until July!

The main difference between the nuanced portions of a course and a major climb is that everyone knows about the climb, and everyone pays attention to it. Somehow, though, we neglect numerous sections due to a first-look dismissal. Both on Zwift and IRL rides and races, small terrain or course changes can end our day prematurely.

Splits and gaps happen most frequently on decisive terrain or after attacks. That is true. Everybody knows this, and everyone is acutely aware of this. Why do we continue to focus so much of our attention on this when we know where the split has the highest probability of occurring? Simultaneously, we almost willfully fail to take advantage of opportunities that are equally as probable.

Natural gaps, a split that occurs spontaneously or naturally rather than due to an attack of some sort, can destroy your chances of contesting the finale of a race without you knowing what happened. The most common causes of natural gaps are a change in wind direction (usually into a crosswind), a series of short but moderately steep hills, and a course change, most often a sharp turn or a significant narrowing of the road. Not being properly positioned for or unaware of these sections could be detrimental to your day.

Group Therapy – Working Together to Bridge the Gap

Obviously, the first way to deal with any natural gap is to be on the good side of the split. For today’s class, we made the assumption that we missed the split and had to bridge to the front group. In previous SDR bridging classes, we focused on bridging from the field to a lone rider or small group of attackers. This situation is a bit of a different animal, as the front group may not be actively trying to get away. It just happens.

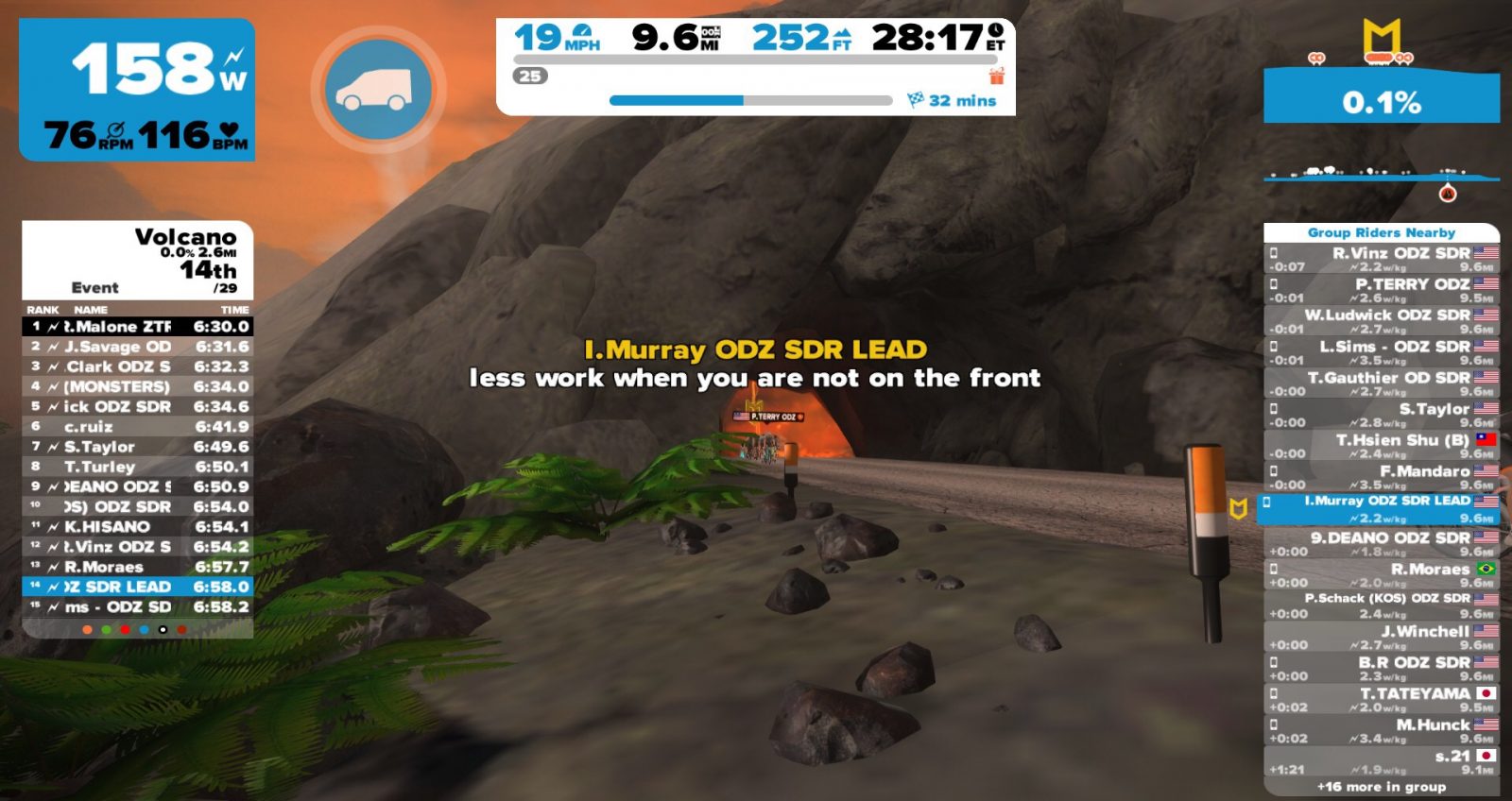

To set up the class, we divided the group into two groups, G1 and G2. While we had planned to split the groups by last name, the small climb on the way to the Volcano CCW route gave us a natural split from the gun. Thus, we played the cards we were dealt and made our groups accordingly.

For the first drill, G1 held steady at 2.0, simulating a natural relative riding pace. I say relative because we artificially cap the pace to try to keep the group together as best as possible. (Also, I have found that hypoxic riders don’t learn very well. They may accomplish the task at hand to end the pain, but they don’t internalize as much. Basically, it’s a little like torture. Thus, we don’t condone that.) G2 began its chase in earnest, holding between 2.5 and 3.0 W/kg. The important part of G2’s chase, though, was working together. As we will see later, there is a difference.

The chase took a while to complete, as we had some other naturally splitting terrain to cope with, and the gap did start at a healthy 35 seconds. The point of the exercise was not to close the gap as fast as possible. The point was to show how to work together to close the gap while limiting any extraneous energy expenditure. By taking turns and keeping the pace steady, those in the front worked a little harder, and those in the draft could rest. All while still closing on the lead group.

We repeated this exercise with G2 being the lead group and G1 having to chase, but with a little different results. We still had the same concept, but the size of the groups were significantly different. G2 was way bigger than G1. We’ll go into the why a little later, though. The result was that someone from G1 had to be sacrificed to the cycling gods. Ok, maybe not sacrificed, but definitely forced to work a bit more. In a race situation, this is where teammates come into play. For our purposes, I took the role of faithful domestique and went to the front to do the work. This allowed my “protected rider(s)” to do less work and be ready for anything as we caught back on the lead pack. This is a very common occurrence, so take advantage of it when possible. The impromptu learning point showed the group the value of communication and working with other riders.

Size Really Matters, Boyz!

After regrouping, we moved on to the second drill. Like the first one, G2 moved to the back, and we allowed a natural gap to open up. Unlike during the first drill, though, riders had to bridge the gap individually, removing the benefit of the draft. The lead group remained at the 2.0 W/kg effort, so we kept that constant.

At this point, you may be thinking that all the G2 riders made it back to the lead group one by one. But you would be incorrect! No, very few riders were actually able to bridge the gap due to a simple matter of physics. In this case, size matters. The much larger lead group, despite rolling at 2.0 W/kg was able to hold speeds equal to or greater than the individual riders could at 2.5-3.0 W/kg. This is due to the effect of the draft on the bunch.

In the end, riders started grouping up at the back, and the small group picked up steam. Along the way, the small group turned into a bigger group, and the draft effect gap began to narrow. Eventually, the size of the chase pack passed a tipping point, and the 2.5-3.0 W/kg was sufficient to rapidly pull back the leaders.

Bringing it Together

After the second drill, we wrapped up the session with a little recap. Unlike previous sessions where we worked on bridging the gap to an attack, the natural gap bridge is something that is completely preventable if you pay attention and maintain a good position. If and when the natural split occurs, try to find some buddies to share the work. A large chase pack has a much better chance to close the gap with a limited expenditure of energy than an individual rider or small group. If you do have to bridge in a solo effort, be prepared for a hard effort or resign yourself to living in no-man’s land for a while before you either complete the bridge or get sucked back into the chase group.

That’s it for this week. Thanks to Castelli for sponsoring the SkillZ and DrillZ Ride. As usual, one lucky US-based rider who completes the ride will be registered for a drawing for some Castelli swag at the end of the month. SkillZ and DrillZ will be off next week but will return on 17 May. Until then, RideOn!