A Challenge Is Born

“Can’t race yourself fit.”

Stefan from my 5v5 Ladder team was once again trying to coach me out of a mid-summer slump. If you’ve ever been on a Ladder team, you know the chat quickly turns into a general discussion of all things Zwift racing. Because Club Ladder runs year-round, those chats never really go quiet in the off-season. Instead, teammates become people you banter with week after week, sharing every small victory and setback.

Stefan’s advice was well-intentioned: take a rest day. I took it as a challenge.

It was July 2024, and I was complaining about being tired for a Thursday afternoon race after doing WTRL Duathlon the night before. That comment got me thinking: what would happen if you ditched structured training altogether and just raced every day?

So I tried it.

I started with 30 races in 30 days. Then 80+ races in 90 days. Before long, I found myself in the “Top 25” most active racers on ZwiftRacing.app. But every three months the stats reset, and it all felt a bit hollow – until December 2024, when Tim from ZwiftRacing.app added a History tab to each rider profile.

Suddenly, full-year totals were visible: races, podiums, wins. Looking back at my 2024 numbers, I saw 251 races, 93 podiums, and 34 wins.

I figured I could do more. And so a 2025 challenge began, aiming for 300 races, 100 podiums, and 50 wins.

The Logistics of Racing (Almost) Every Day

I’m based in Chicago, and most of my racing happens during lunch breaks – assuming meetings allow. If I have calls between 11:30 and 14:30 CST (17:30–20:30 UTC), racing options shrink fast. With many low-attendance community races removed from the calendar, meaningful racing outside those windows is limited, aside from the hourly zRacing events.

Weekends were a particular challenge with young kids in the house. Saturday activities became stressful once “it would be nice to race today” turned into “I have to race today.” Knowing there was only one race per hour created real friction at home.

Zwift’s lack of on-demand racing becomes trying, particularly in these low-popularity slots. Unlike most video games, there are no bots and no instant lobbies – you can only race at a set time against whoever shows up. That sometimes meant racing late in the evening in a pen where the only other rider dropped out. At that point, I’d happily take robots over an empty pen!

There were days I raced alone just to keep the streak alive. Occasionally, I leaned on formats like Tiny Races, where multiple short races count individually. It would be easy to inflate totals that way, but that wasn’t the goal. The goal was more simple: race as often as possible and see whether fitness would follow.

Chasing Podiums and Wins

So, how to judge success? Zwift racers joke about “little virtual trophies,” but there’s no denying they’re motivating. Even if no one else cares who won in Crit City last Tuesday, seeing a podium on your profile feels good.

The problem is defining what actually counts.

Zwift has long struggled with multiple results sets thanks to disqualifications and the opt-in nature of ZwiftPower. If you’ve raced on Zwift, you’ve probably seen an eighth-place in-game finish turn into second-place on ZwiftPower. That’s a podium. Hooray! But should it be?

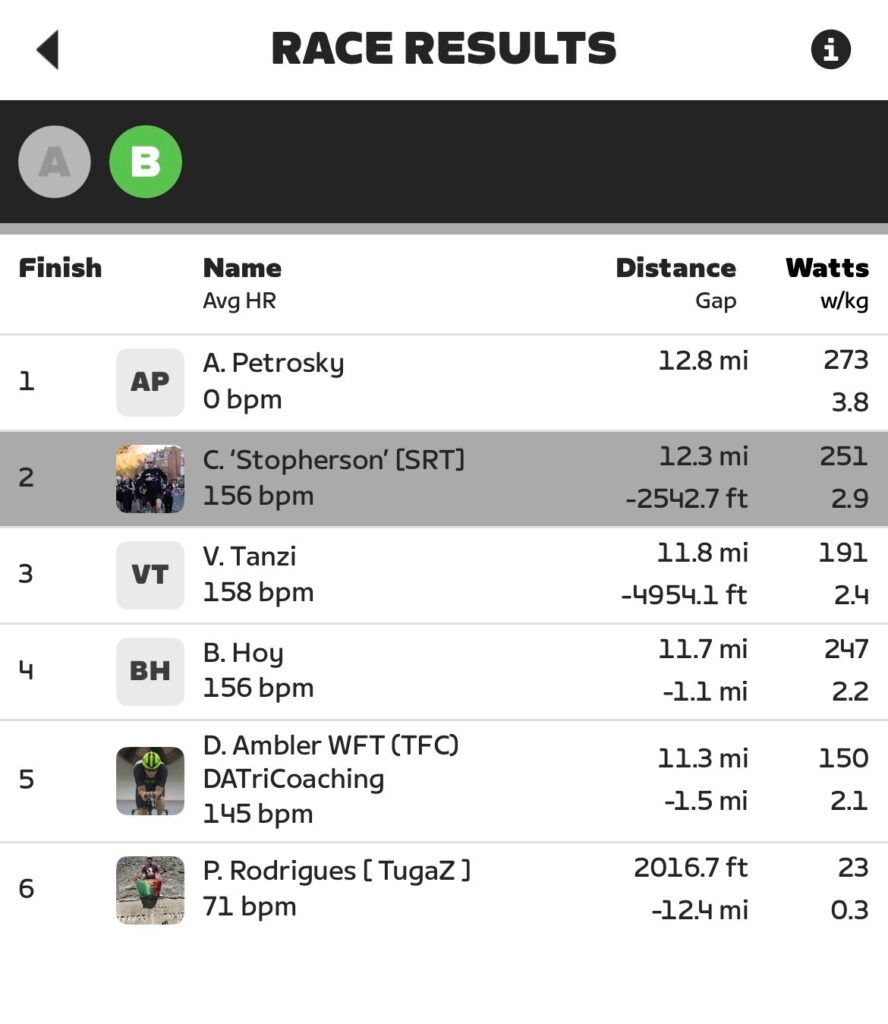

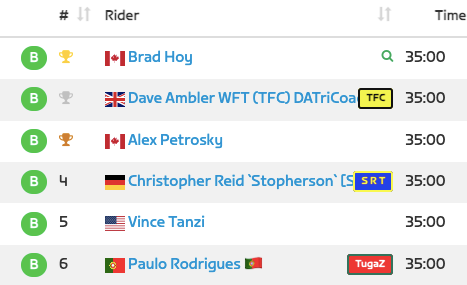

Even worse is ZwiftPower’s time-based randomization – introduced to prevent racing in group rides – which can occasionally interfere with legitimate race results. Over the year, I lost more than a few podiums in WTRL Duathlon due to mismatches between systems:

Yes! Alright! 2nd Place! Until ZwiftPower weighed in with the sad trombone…

At the same time, does a third-place finish in a four-rider field really deserve the same excitement as third out of 70? And worst of all, a 1-of-1 finish counts as both a win and a podium when neither really happened.

Between races that didn’t count correctly and others that arguably shouldn’t count at all, podium stats became more noise than signal. Fun to look at, but not something to judge success on. Eventually, I dropped podiums and wins from my annual goal just to reduce frustration.

Fortunately, new APIs from Zwift now allow third parties to pull results directly from Zwift itself, meaning we can finally see results for non-ZwiftPower riders. ZwiftRacing.app has already integrated this, and ideally other organizers will follow. Soon, “if it’s not on ZwiftPower, it didn’t happen” may be a thing of the past.

A Year of Ranking and Categorization Systems

Over the course of the year, I raced under nearly every system Zwift currently uses: Category Enforcement (CE), Zwift Racing Score (ZRS), legacy ABCD categories, vELO, age-based pens, and even events with no categories at all.

None of them are perfect, but some are clearly better than others.

Category Enforcement (CE)

Category Enforcement does a good job limiting climbing speed, which helps make hilly courses feel fair. Power-based categories are a boon to riders near the top of their category, but those near the bottom are often doomed to uncompetitive races. On flat courses, unlimited watts in a w/kg system means some heavy riders are simply unmatchable.

Having raced on both sides of the dividing line in ZRL last year, I can say with confidence that being at the top of a category is definitely more fun. As a “barely B” rider, I struggled mightily under CE, but found a niche in crits where I could just about hang on and occasionally sneak a podium or win.

Legacy “ABCD” Categories

Legacy ABCD events are increasingly rare, and when they do appear, they often feature baffling rule sets: no pen enforcement, “see everyone” enabled despite staggered starts, and even late joining allowed. Even as someone who races nearly every day, I found myself irrationally irritated by a late joiner “winning” after only riding the final two kilometers – often from the wrong category. It’s hard to imagine we ever raced like that, but Zwift has clearly come a long way!

Zwift Racing Score (ZRS)

Power-based categories are mostly gone now that Zwift Racing Score was adopted for most races in 2025. ZRS aims to improve matchmaking using results, but frequent racing exposes a key weakness: inflation. Unless you finish dead last, score losses are minimal. Race often – especially in small fields – and your score tends to drift upward over time.

My own experience reflected this. Despite modest power numbers, I quickly found myself above 700 ZRS, locked into top pens against former A+ riders. Meanwhile, riders I’d been competitive with in the lower half of ZRL B fields under CE spent much of the year hundreds of points lower. Climbing against riders with 900+ ZRS capable of holding 6+ w/kg was a brutal reminder of why we had power-based systems in the first place!

ZRS is a major step forward, but if it takes ~100 races to settle and most riders only race once or twice per week, it may be a long time before the majority of riders truly find their level.

vELO

Let me preface this by saying I really like vELO as a concept. It has become my primary barometer for race performance because it answers a simple question: did you perform better or worse than expected, given the competition?

As a categorization system, vELO has meaningful advantages over both CE and ZRS. It avoids hard power caps while still considering power enough to prevent legacy A+ and C riders from landing in the same pen. The prediction model’s terrain modifiers are especially impressive, accurately identifying where riders with certain power profiles will struggle. (A rider who’s Gold with no sprint, for example, might be classified as Silver on Crit City.)

Unfortunately, race series can’t use those terrain-adjusted values for pen allocation. Worse, points-based series will ignore them entirely. I learned this the hard way by losing more than six months of vELO progress in just a few climb-heavy Dirt Racing Series events back in the Spring!

vELO 2.0, slated for 2026, will absolutely tighten this up. Today’s vELO is great, but the new version promises to be something really special.

Age-Based Racing

Age-based formats like WTRL Duathlon and the Inox Masters League have promise, but Zwift’s five-pen limit creates complications when more than five age groups race together. Results rely on post-race ZwiftPower adjustments, leaving riders unsure of their finishing position until well after the race ends.

There’s also no power limit, so, as with ZRS, you can end up with D and A+ riders in the same pen. That’s rarely compelling for the former, but with popular series like Inox Masters running short, punchy races, many riders can at least feel competitive. These were terrifying affairs as I did them, but afterwards, I remembered them fondly. The definition of Type 2 fun!

Everyone Together

Somewhat surprisingly, I’ve come to believe that the best categorization system might be none at all.

Some of the most enjoyable races I did all year featured “everyone in E” with a ZRS range of 0–1000. These weren’t mass-start events that still created winners and losers based on who could hang with the category above. Instead, they were true “everyone together” races. Riders naturally sorted themselves into groups, and success was measured by beating the riders around you – not chasing a podium.

HERD Winter Racing deserves special mention here. Those Friday events were consistently some of the most engaging races on the calendar.

The Advanced Pen Hack

While not a separate categorization method, the Advanced Pen felt like a revelation compared to the chaos that often defines zRacing. With a 650+ ZRS requirement, fields were more predictable and largely free of sandbaggers and “October Surprise” riders with artificially low scores after a summer outdoors.

Racing against 900+ ZRS riders was still brutal, but the hard cutoff minimized downside for riders near the bottom. When you’re predicted last, vELO and ZRS losses are small, and with stronger riders intentionally shedding points, you could even gain vELO while finishing near the back.

It almost feels like a hack: if you want to look good on paper, race Advanced Pen. Just be prepared to get dropped!

Unranked Racing: An Opportunity Area?

All of this raises an obvious question: why don’t we have more unranked races on Zwift?

Outside of WTRL Duathlon, Team Time Trials, and Chase Races, almost everything “counts.” That creates a real disincentive to race when you’re anything less than 100%, which is a shame, because racing against others is often the strongest motivator Zwift has.

Zwift’s “Friday Night Fun Races” were a welcome exception. Dinosaur costumes, big-head mode, tricycles, and sub-20km races sounded like an excuse to take it easy. Instead, three of my top five all-time 20-minute power efforts came from those events.

There’s something freeing about knowing there are no consequences for blowing up. I’d love to see more races like this appear on the calendar in 2026.

So – Did Racing Every Day Improve Fitness?

By January 2025, I was a recently relegated C rider adjusting to a new Zwift Ride setup and learning to sprint properly after switching to clipless pedals. By mid-year, I was solidly back in B, winning races and feeling confident in my sprint (though naturally climbs will forever remain an Achilles’ heel).

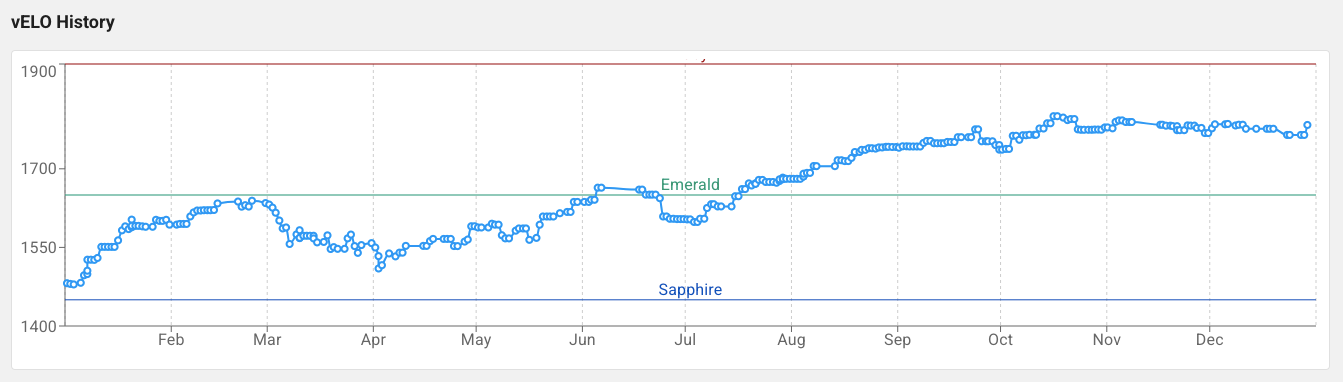

On paper, I improved. vELO rose from low Sapphire to high Emerald. ZRS climbed from the low 500s to over 700. Estimated FTP (eFTP) jumped from 298 in 2024 to 323 in 2025. I was setting new power PBs almost weekly.

The grind, in chart form.

In practical terms, though, the picture was more mixed.

Racing every day makes you very good at racing – specifically at 25–30 minute efforts. Over the year, I became exceptionally good at standing up and driving high watts for 30–60 seconds to close gaps.

But being good at repeated anaerobic surges doesn’t build endurance. Long rides all but disappeared, and my weight actually increased as the year wore on. While I might comfortably beat my former self on Glasgow Crit Six today, I’m fairly sure “old me” would have the edge on Alpe du Zwift.

In racing nearly every day, I didn’t become a better all-around cyclist. I became better at Zwift racing.

Year-End Numbers

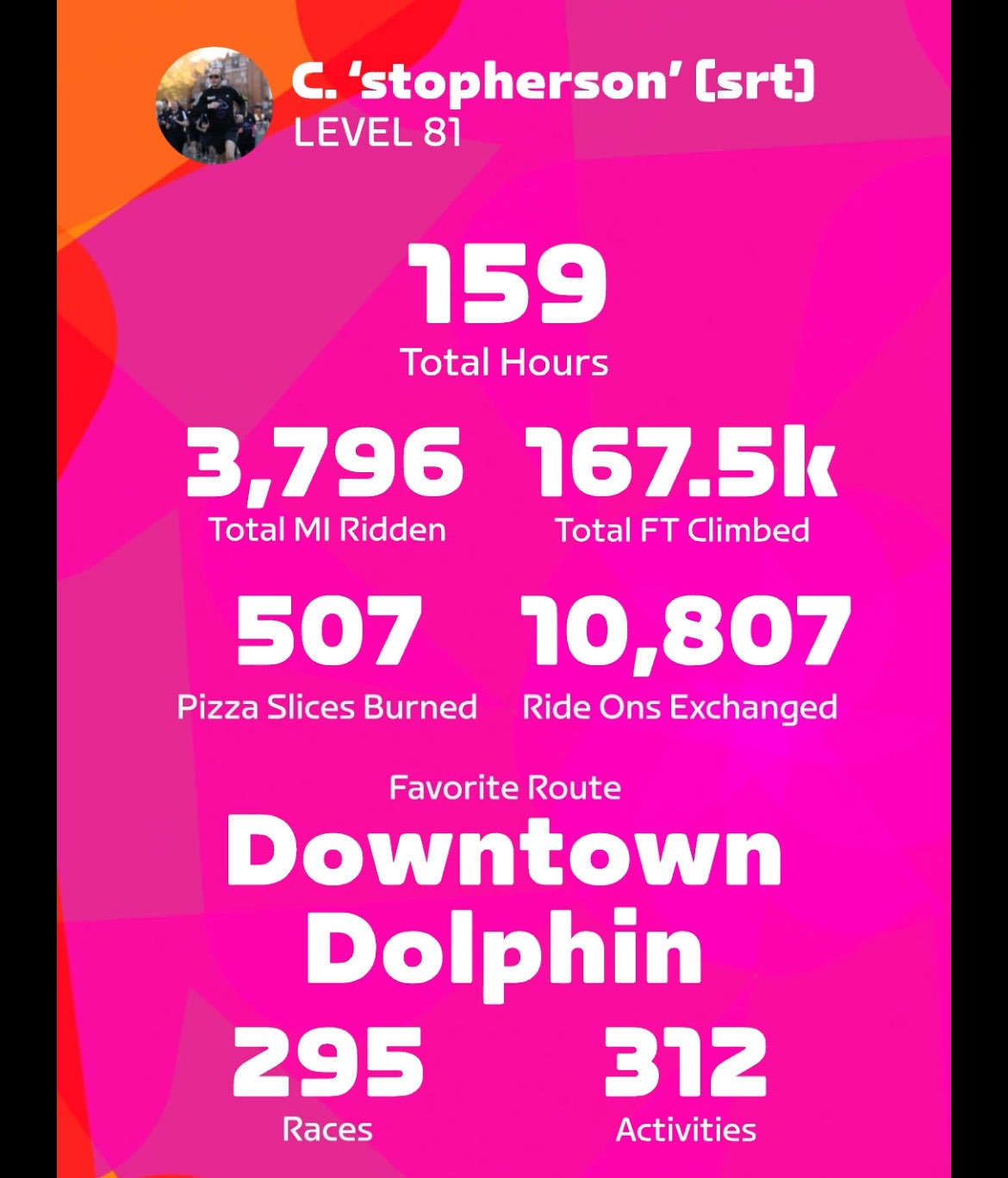

According to ZwiftRacing.app, my 2025 looked like this:

- 313 races

- 58 wins (19%)

- 152 podiums (49%)

- 1 DNF (A black mark!)

- Min vELO: 1479 Sapphire

- Max vELO: 1800 Emerald

- Final vELO: 1783 Emerald

Racing was nearly all I did, which my somewhat embarrassing Zwift Spinback highlighted in clear detail!

Zwift Spinback highlighted 2025’s depravity. But what was I doing on those 17 rides that weren’t races?

Final Thoughts

Racing can absolutely make you fitter… for racing. But when it crowds out everything else, something gets lost.

Over the year, I skipped group rides, fun activities like The Big Spin, tours like Tour de Zwift and Tour of Watopia, and much of the social side of the platform. Instead of riding primarily with my clubmates, I became a lone wolf – joining whatever race fit the time slot I had available that day.

My interactions with other riders dwindled to a “GLHF” in the pen or the occasional dinosaur joke on Friday nights. Zwifting became an obsession focused on results and metrics rather than fun and fitness. At some point, it kind of stopped being fun.

I like to think both Stefan and I were right. You can race yourself fit – but if racing comes at the expense of everything else, you may end up fitter at Zwift and poorer at things that matter even more.

So this year, I’ll remember to keep it light. We’re all here just trying to get fit, blow off some steam, and hopefully have a good time doing it. Ride On 2026!