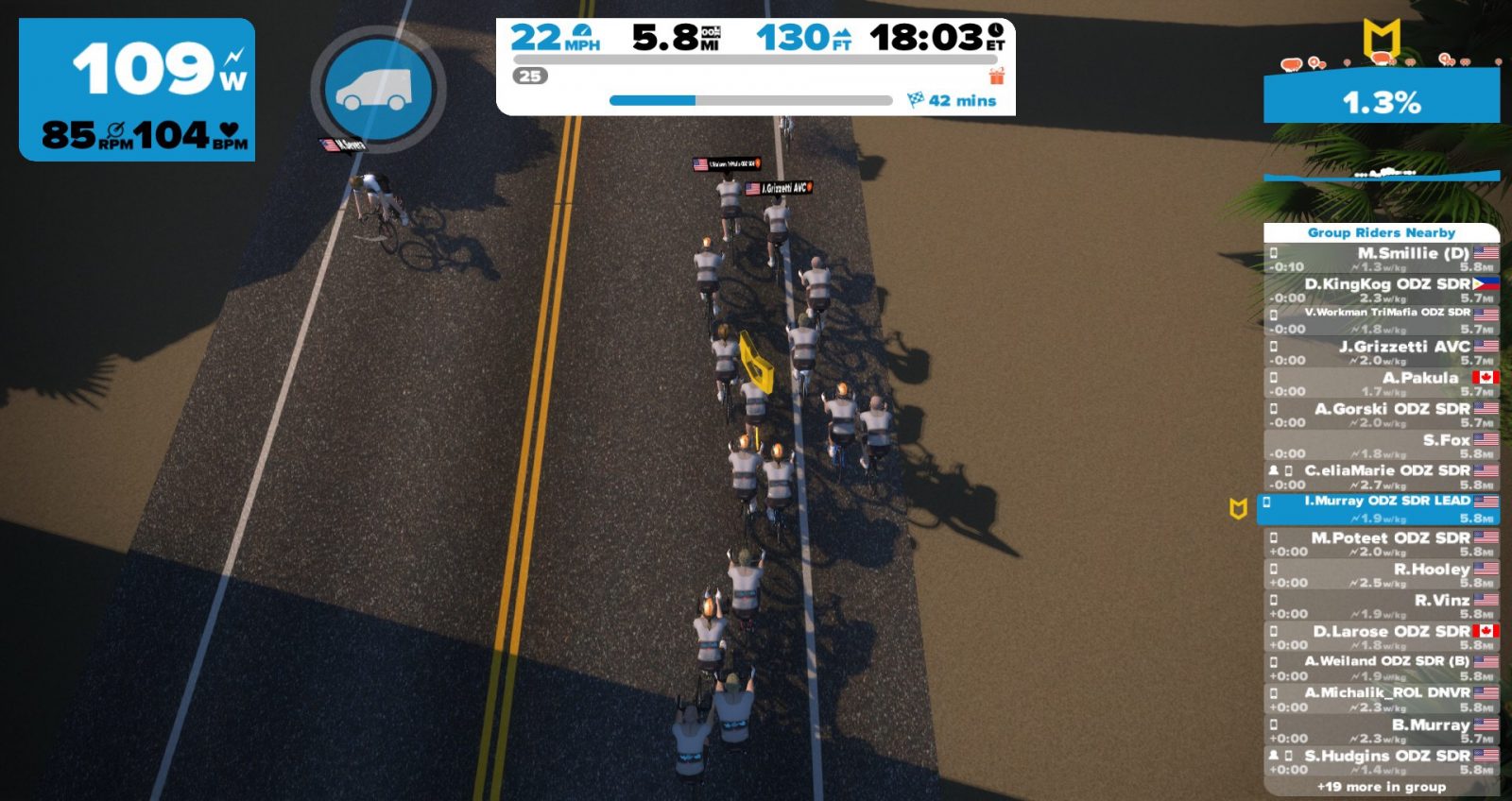

Castelli SkillZ and DrillZ Ride, 29 March – When we talk about decisive terrain, we often discuss Alpe d’Huez, Box Hill, or the Epic KOM. Sure those are decisive, but few races or rides actually have that sort of a significant terrain feature that everyone recognizes as important. More often than not, a small terrain feature turns out to be critical to the outcome of a race. It can be a type of road, a series of technical turns, or a very technical descent. Often, though, it comes down to a short, punchy climb that disrupts the normal flow and chase of the pack. As many of our Zwift courses have one of these climbs towards the end of the race, I thought we should cover it.

To see today’s lesson and hear the instructions, go to Zwift Live by ODZ on Facebook or watch it below:

Before we talk about attacking the short, punchy climbs, let’s examine what makes them special. First, these types of climbs favor powerful riders but not big riders. They also do not favor traditional climbers due to being short in duration, limiting the role of gravity over time. In terms of power output, sprinters and TTers are generally outmatched by those riders with a comparatively high 5-minute power, despite not having the best sprint or 20-minute power. Above all else, though, punchy climbs favor the tactically savvy and the brave attackers. I think that is what draws people to the Spring Classics above other one-day races… throwing caution to the wind is often rewarded, making those races so much fun to watch.

The Warm-Up

Like usual, we started our day with ten minutes of warm-up, practicing maintaining our position within the group. During this period, I reinforced the importance of this concept, as it would come into play later in the class. As we closed in on the end of our warm-up, we discussed the three key points for making a successful move on a punchy climb: momentum, positioning, and attacking through the crest of the climb.

Momentum

Momentum, while not the most important consideration, certainly can have a significant impact on how you handle the short, punchy climbs. As the climb approaches, you need to carry some speed into the base of the climb. It is a very simple concept because you are going to lose speed as soon as the road pitches up. Having some momentum will help you get up the first portion of the climb without losing touch with the front of the group. If you don’t carry speed into the climb, it can become very hard very quickly, and you will have to begin burning matches to get going again.

To show the value of momentum, we performed a simple drill. As we approached the small hill, we dropped our effort from 1.5 to 1.0 W/Kg. When the road turned upward, our speed dropped significantly, and it took a considerable amount of effort to get moving at speed again. We repeated the drill two more times, the first maintaining a constant speed of 1.5 going into the climb, and the second accelerating into the base of the climb. The third iteration showed that simply accelerating a little bit, from 1.5 to 2.0, allowed riders to get up and over the climb a lot easier.

Positioning

Positioning was our second topic of the day, and I would argue that it is key to either attacking or staying with the group. Speaking first about those who struggle with climbing, positioning can make or break their chances to sprint for the win. Eight years ago, Mark Cavendish showed that a pure sprinter could win Milan-San Remo. To do so, he had to get over the Poggio and the Cipressa with the lead group. If he had not been able to do that, he would have had zero chance to win. Cav trained hard all winter, but no amount of training would convert him from a sprinter to a climber. That’s not how his muscle fibers are made up. He’s a sprinter. What he did do, though, was make himself a less crappy climber and develop a plan. As the lead group approached each of the numerous climbs in the last 100K, his team brought him to the front, driving the pace to ensure that he could start each climb at the very front of the group. As the road kicked up, Cav slid back, not in an “I just dropped an anchor” way but more of a slow drift. While he may have lost his position at the front, he never lost contact with the group. He and his team repeated this drill over and over as each climb approached. The infernal pace leading up to each climb discouraged attackers, and Cav made it to the finishing straight and outclassed the field.

Now, I am not saying that this technique will work every time, but it is proven quite often. We practiced this technique a couple of times, dividing the group into two, with each group taking turns being the sliders. Besides allowing weaker climbers the chance to stay with the group, some found it a useful tool to save some energy, too. If you know that the decisive point will not be on the climb or immediately after, you can use the drift to conserve and then make your way back to the front of the group on the descent or the subsequent flat section.

For those wishing to attack, positioning is equally as important. More so in IRL racing than in Zwift, the punchy climb often creates a bottleneck that can prevent a rider from attacking or responding due to being blocked by slower riders. During this year’s Spring Classics, many of the favorites found themselves on the back foot due to being positioned too far back when a crash occurred or a rival attacked. That resulted in burning extra matches to chase or even the loss of the race.

We ran through a couple drills highlighting the difficulty of attacking when out of position to show why it is the less than optimal tactic. Unfortunately, most people understand that positioning is of the utmost importance, so that is why we often see the pace lift considerably as we approach these punchy climbs. Everyone wants to be at the front.

Attacking through the Crest of the Climb

Assuming you carried momentum into the climb, were well-positioned, and wanted to launch the brave attack, we now come to the third and final point of instruction of the day, attack through the crest of the climb. Attacks up these short, punchy climbs have to be well-timed and dosed. If you attack too early or too hard, you will not have enough to sustain the advantage, leaving your effort to be tagged as just another foolish move. However, attack from a point on the climb where you can sustain the effort through the crest and the first third of the descent, and your move could very well go down as something of legend. This is easier said than done, though. As we arrive at the top of a climb, most of us ease off on the pedals, drop our heads, gasp something about wanting to die, and attempt to catch our breath and drop our heart rate. If you are on the attack, though, you will have likely just given back everything you had taken. By holding the effort through at least the first third of the descent, you may actually stretch your lead, as you will be bombing down the hill while the chasers continue to climb. Sure, they will benefit from the descent, but you will have taken time that they may not be able to pull back if the terrain does not kick back up while they are on the descent.

The Watopia Esses are perfectly suited to this type of attack. If you can carry a ten second advantage into the last descent toward the finish line and really hammer the next 400 meters or so, you will be very tough to pull back without a Herculean effort on the part of your adversaries. The extra seconds you will gain on the bunch is just that much more effort they have to put out relative to you.

Conclusion

We ended our Castelli SkillZ and DrillZ session after practicing the last technique a few times and began our cool-down. As we wrapped up, we revisited our points from the day. First, carry some momentum into the short, punchy climbs. The length and often rapid change in incline do not allow much room for error. Rolling in with momentum gives you the best opportunity to do what you need on the climb. Second, positioning is key. Be where you need to be. If you want to avoid being dropped off of the back, get to the front and drift back on the climb. If you plan to attack get to the front and try to stay in the first ten wheels. Third, carry your attack through the first third of the descent. The extra effort will allow you to consolidate your attack and may give you just those few extra seconds you need to stay away.

That’s it for now. Thanks to Castelli Cycling for sponsoring today’s ride, giving away some swag to one lucky US-based rider who completed it, and thanks for joining. Until next time, Ride On!